I really should have gone into some kind of mathematics. My father would be so proud.

The longer i live, the more i realize that almost every aspect of human existence lies somewhere on a giant bell curve. Having a shitty day? Start keeping a log and i will guarantee you that you have just as many crap days has you have really good days with a whole mess of mediocre days in between. Feeling like you never have any time? Turns out, a vast majority of your time is spent sleeping or working with only the tiny edges being devoted to the things you really want to be accomplishing. Think that person is a jerk? You're probably right.

Unfortunately for my father, an accountant of no small skill, my mind has never had a propensity towards numbers, so my recognition of these patterns lies almost solely in the sociological forums. After interacting with the hundreds of thousands of people in my life, it was almost inevitable that i'd start to pick up on the similarities within the intricacies. Human beings, like snowflakes, are unique; no two are completely identical. Like snowflakes, however, they all share a huge number of similarities. It is the beauty of the individualism that drew first drew me to my brief time studying psychology and the simple, logical nature of their similarities which makes them so easy to understand. Much like how i assume numbers make sense to my father.

"X" is still not a number, Dad.

Your personality can be plotted on a bell curve. The edges are the little minutiae which make you unique while the larger area you share with most other folk. Whether it agrees with the self-esteem programs we are taught in school or not, a huge majority of people will respond in a predictable manner when presented with a certain set of predetermined circumstances. It doesn't make you less of a person, i promise.

Stereotypes are generally formed because of the bell curve. Young kids are usually snotty. Old folk are often poor drivers (for a great many varying reasons). Babyboomers like The Beatles. Mac users think they're better than you. The trick, then, is to acknowledge that the edges of the curve exist and to give everyone you meet the benefit of the doubt. Don't assume. Use the Golden Rule.

I mention this, my reader friend, not to try and describe some great Truth that has been heretofor remained undiscovered. I am simply attempting to explain one of the ways i look at the world. One part of my Family Dark is a certain depressive nature which, while often lending itself to a lovely artistic bent, just as easily propels the sufferer in front of a bus. For me, i strive to make the world understandable. Once i ascertain a certain Truth about the nature of humanity or society or politics or physics or anime, i can become comfortable with it.

As Murphy once famously stated, 90% of everything is crap. There's not a lot you can do about it. Personally, i take comfort in that knowledge. Its just another fact of life to be dealt with or ignored as you see fit.

Always remember that its the 10% that makes life so amazing. Make the most of it.

Monday, October 26, 2009

Thursday, October 22, 2009

Houses & Homes, Pt. 3

The summer sun beat hard down on his upturned face as he mopped his brow with his shirtsleeve. The burning eye in the sky told him that it was noon and he plopped down on the slowly growing pile of wood next to him and lit a cigarette, closing his lighter with a small flourish.

The winter had been a long one, leaden with tears and heavy glances. She had not understood his epiphany, that the house they had built was built in error – out of a need for security more than a desire for satisfaction. She had screamed, cried, pleaded, thrown things at him, upturned furniture. In the end, he had been forced to drive her from the building and back to her parents' home, her pack and belongings slung over his own shoulders, her weeping being their traveling tune.

The rest of the spring was spent cataloging the nature and quality of the house. He didn't spend another night in its walls, but pitched a shelter on the edge of the woods and cooked his repasts over an open flame. Once the meticulous lists were completed and he was sure that he had learned every error and how it had come about, he began deconstruction; the first day of summer.

Plank by plank, nail by nail, pillow by chair, the house was torn limb from limb and thrown into a great pile. The burn in his arms was cathartic, the sweat on his brow soothing to his bruised mind. As the pile grew, so to did his satisfaction with this new-found life he was “building” for himself. Every board felt like a small revelation, the naked wood underneath describing the nature of all the falsehood he had inadvertently found himself believing. When the pile stood as high as he and the remains of the house little more than a skeleton of sun-bleached timber, he finally felt whole again.

Cigarette finished, he stood, took up his hammer in his belt, went back into the carcass. Climbing, monkey-like, muscles taut and straining, he ascended the structure to the apex and began the long – but last – step of disassembling the framework from the top, down. Overtaken by the fever of determination, he did not stop for rest or sustenance until he finished, leaving only the foundation posts in place. Two days he spent crawling over the final remains and he finalized the entire enterprise by hewing off the last posts at the base.

The garden had long returned to its natural state, as if it had never felt the touch of the hoe; the fence surrounding it had been removed and cast into the pile. The entire structure removed, the ground where it had once stood was now level and bare, the only visible evidence of its existence the expanse of dirt in place of the surrounding grass. The paving stones that had once made up the walk were pulled up and planted, on edge, in the earth around the pile, creating an uneven circle about it. The pile itself, meanwhile, had been carefully altered, with certain longer boards and pieces replaced so as to protrude out- or upward. On some of these poles, furniture was skewered. On others, blankets were stretched or other boards lashed. This final effort produced a horrific effect on the ramshackle monolith. It stood halfway between the woods and the empty plot, grinning insanely, an ominous warning to passersby of events unknown.

The winter had been a long one, leaden with tears and heavy glances. She had not understood his epiphany, that the house they had built was built in error – out of a need for security more than a desire for satisfaction. She had screamed, cried, pleaded, thrown things at him, upturned furniture. In the end, he had been forced to drive her from the building and back to her parents' home, her pack and belongings slung over his own shoulders, her weeping being their traveling tune.

The rest of the spring was spent cataloging the nature and quality of the house. He didn't spend another night in its walls, but pitched a shelter on the edge of the woods and cooked his repasts over an open flame. Once the meticulous lists were completed and he was sure that he had learned every error and how it had come about, he began deconstruction; the first day of summer.

Plank by plank, nail by nail, pillow by chair, the house was torn limb from limb and thrown into a great pile. The burn in his arms was cathartic, the sweat on his brow soothing to his bruised mind. As the pile grew, so to did his satisfaction with this new-found life he was “building” for himself. Every board felt like a small revelation, the naked wood underneath describing the nature of all the falsehood he had inadvertently found himself believing. When the pile stood as high as he and the remains of the house little more than a skeleton of sun-bleached timber, he finally felt whole again.

Cigarette finished, he stood, took up his hammer in his belt, went back into the carcass. Climbing, monkey-like, muscles taut and straining, he ascended the structure to the apex and began the long – but last – step of disassembling the framework from the top, down. Overtaken by the fever of determination, he did not stop for rest or sustenance until he finished, leaving only the foundation posts in place. Two days he spent crawling over the final remains and he finalized the entire enterprise by hewing off the last posts at the base.

The garden had long returned to its natural state, as if it had never felt the touch of the hoe; the fence surrounding it had been removed and cast into the pile. The entire structure removed, the ground where it had once stood was now level and bare, the only visible evidence of its existence the expanse of dirt in place of the surrounding grass. The paving stones that had once made up the walk were pulled up and planted, on edge, in the earth around the pile, creating an uneven circle about it. The pile itself, meanwhile, had been carefully altered, with certain longer boards and pieces replaced so as to protrude out- or upward. On some of these poles, furniture was skewered. On others, blankets were stretched or other boards lashed. This final effort produced a horrific effect on the ramshackle monolith. It stood halfway between the woods and the empty plot, grinning insanely, an ominous warning to passersby of events unknown.

Tuesday, October 13, 2009

Avuncular, Yes I Am

I paced around the waiting room in a frenetic sort of mania. My mother sat calmly at the little round table, reminiscing with her friend about their past pregnancies. I tried to sit at my computer to find a way to fritter some time, but the communication between my mind and the information i was taking in was muddled. I couldn't concentrate. It took me forever to finagle a wireless connection.

A friend came and met me. I smoked a cigarette outside, calmed by the action and her presence. The unholy amount of nervous energy coursing through my limbs quieted, slowed to a trickle.

Back in the ward, i found out i had missed Steve coming out. Everything was going fine. Allyson had been given an epidural and was calm and pain-free. Radius of dilation indicated that our wait would not be long. We settled in for the home-stretch.

Heh. Yeh, right. My nervous energy came back full force in no time and i was soon forced up from my computer to patron the sidewalk outside. I predicted - based on Murphy's Law and my own piss-poor luck - that the baby would be born while my friend and i were gone. I was almost right. Shortly after i finished my smoke, my phone vibrates:

From: Steve

Check your email!

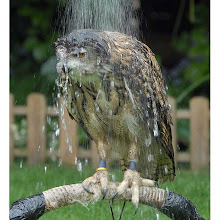

We run back upstairs, i gibber something about emails and Steve to my mom and log into Gmail. Lo and behold, what should my eyes see but this little angel on my monitor:

And dear me, what a sight.

A friend came and met me. I smoked a cigarette outside, calmed by the action and her presence. The unholy amount of nervous energy coursing through my limbs quieted, slowed to a trickle.

Back in the ward, i found out i had missed Steve coming out. Everything was going fine. Allyson had been given an epidural and was calm and pain-free. Radius of dilation indicated that our wait would not be long. We settled in for the home-stretch.

Heh. Yeh, right. My nervous energy came back full force in no time and i was soon forced up from my computer to patron the sidewalk outside. I predicted - based on Murphy's Law and my own piss-poor luck - that the baby would be born while my friend and i were gone. I was almost right. Shortly after i finished my smoke, my phone vibrates:

From: Steve

Check your email!

We run back upstairs, i gibber something about emails and Steve to my mom and log into Gmail. Lo and behold, what should my eyes see but this little angel on my monitor:

And dear me, what a sight.

Monday, October 12, 2009

Houses & Homes, Pt 2

“Home”.

The word continued to ring in his head. Something about it felt wrong. False. He replayed the argument he had had with her over and over again on his long trek back from the annual meeting in the glade. She hadn't wanted him to go, claiming that their journey was over, that they had built a home for themselves and he had no reason to return to his old life, his old friends. The fight had been long and bitter and, in the end, he had slung his pack over his shoulders and slammed the front door shut to block out the sound of her weeping.

He felt alive again on the trail, in his old ways, to see his old friends. He had hunted, reveling in the game; the chase, the kill, the blood on his hands. The taste of meat, after almost a year of nothing but vegetables and bread, had revitalized something deep and forgotten inside of him. He arrived in the glade full of good spirits and to the triumphal thunder of his comrades in wandering. For seven days they sat around the fire, swapping stories and sharing their meals. The musician had sacrificed valuable pack-weight to bring his guitar, and the music harmonized them. The brute had brought a jug of his best whiskey, and the liqueur cheered them. The lover had brought his best stories from the far reaches of the land, and his words challenged them. He himself had brought a sample of the tobacco he had been growing that year, and the smoke soothed them. All too soon, though, their time was over and they bid each other bittersweet farewell and went their separate ways.

Smoke traced a spiraled, parabolic arc, dissipating slowly, following the path of his discarded cigarette. His house was in sight and she hated his smoking. He had finished the last of his meat, not bothering to hunt so close to his property, knowing that he'd not be allowed to keep any of it. He sighed, readjusted his pack, and walked up the path to the front door.

His reception was terse, but civil, and the cold shoulder only lasted until dinner, which consisted of a simple fair of vegetable stew and sourdough. He ate two helpings and didn't taste any of it.

The moon rose on their bodies entwined, her pale skin turned to porcelain by the ghost light. She was warm and passionate, burning for his presence, his arms wrapped around her. He prayed she didn't notice his hollowness. The motions were right, each caress practiced to perfection, the words coming in just the right order, at just the right time, but his mind was in the sitting room.

The sitting room was cedar.

The outside walls were sided with oak. The bedroom was cherry. There was no stonework. No willow. No ebony. This was not his house.

And he knew, in that moment, that this life was over.

The word continued to ring in his head. Something about it felt wrong. False. He replayed the argument he had had with her over and over again on his long trek back from the annual meeting in the glade. She hadn't wanted him to go, claiming that their journey was over, that they had built a home for themselves and he had no reason to return to his old life, his old friends. The fight had been long and bitter and, in the end, he had slung his pack over his shoulders and slammed the front door shut to block out the sound of her weeping.

He felt alive again on the trail, in his old ways, to see his old friends. He had hunted, reveling in the game; the chase, the kill, the blood on his hands. The taste of meat, after almost a year of nothing but vegetables and bread, had revitalized something deep and forgotten inside of him. He arrived in the glade full of good spirits and to the triumphal thunder of his comrades in wandering. For seven days they sat around the fire, swapping stories and sharing their meals. The musician had sacrificed valuable pack-weight to bring his guitar, and the music harmonized them. The brute had brought a jug of his best whiskey, and the liqueur cheered them. The lover had brought his best stories from the far reaches of the land, and his words challenged them. He himself had brought a sample of the tobacco he had been growing that year, and the smoke soothed them. All too soon, though, their time was over and they bid each other bittersweet farewell and went their separate ways.

Smoke traced a spiraled, parabolic arc, dissipating slowly, following the path of his discarded cigarette. His house was in sight and she hated his smoking. He had finished the last of his meat, not bothering to hunt so close to his property, knowing that he'd not be allowed to keep any of it. He sighed, readjusted his pack, and walked up the path to the front door.

His reception was terse, but civil, and the cold shoulder only lasted until dinner, which consisted of a simple fair of vegetable stew and sourdough. He ate two helpings and didn't taste any of it.

The moon rose on their bodies entwined, her pale skin turned to porcelain by the ghost light. She was warm and passionate, burning for his presence, his arms wrapped around her. He prayed she didn't notice his hollowness. The motions were right, each caress practiced to perfection, the words coming in just the right order, at just the right time, but his mind was in the sitting room.

The sitting room was cedar.

The outside walls were sided with oak. The bedroom was cherry. There was no stonework. No willow. No ebony. This was not his house.

And he knew, in that moment, that this life was over.

Saturday, October 10, 2009

Houses & Homes, Pt 1

In a place and a time not too far from where we live, live people not too far from what we are. The people are not complicated, their labors are not in vain. They eat, drink, and find satisfaction in their work. For these simple folk, man's greatest achievement is the construction of a home; a domicile for him and his. This is the story of one young man in that place.

===

He'd always loved his parents' house. It was older than he was and had all the eccentricities that come along with such age. It was worn down to comfort by life and years. When something broke, his mom and dad worked hard to fix it again. It was these aspects that appealed to him; the house was not perfect, not elegant by most means, but it was solid, beautiful, and warm. He loved his house.

But it was not his house.

When the time came, as it does in the life of every young man, he packed up his belongings, slung them across his back, kissed his mother good-bye, and walked out the front door to make his own way in the world and, one day, to build his own home. In addition to the supplies necessary for survival, he carried with him tools: shovel, axe, lighter, rope, saw, hammer. These he would want eventually, when he found just the right plot of land, but they were not the most important tools he carried with him.

In his hands, he had the skills he had acquired over his lifetime, some more useful than others. With these skills, he made his way – foraging, bartering, working, doing whatever he needed to do to continue on his journey. His parents were intelligent, hard-working folk and they had done their best to ensure that he had been given every skill he would need to survive on the road. He possessed a quick, nimble mind, a clever eye, and an easy, sociable nature. No feat seemed beyond his reach.

I tell you this not merely to inform you about this young man's nature, but also as a contrast to the second important tool that he carried with him. In his mind, as most people do, he held a blueprint of the house that he would one day build and a list of all the materials he would want to use in the construction. Some of the ideas he'd gotten from his parents' house, some, from his friends. A few of the concepts were original ideas, never before used in a house of which he knew. Never satisfied with the staples, we was consistently scrapping certain materials in favor of different, less common ones. It was this never-ending search for the perfect construction that drove him, both forward and slightly mad.

===

There are always a lot of people on the road, going all sorts of places in all manners of conveyances. Many of his friends traveled with him for a long time, making discoveries, experiencing hardships, laughing. A few quickly found their plots and settled down to build. He visited as often as he could, offered his help where desired. Eventually, they all parted ways, needing to find their own separate paths.

He kept up communications with a few of them, penning long letters every few months. Once a year, they gathered again in the old glade, trading stories and ideas in the glow of embers and starlight, but every year, fewer returned.

Loneliness began to color his frustration. Everyone around him seemed to have found their ideal settings and had settled down, but he knew that their decisions were not his own and that he could never be happy with their lives. He trudged on.

One day, while picking up some supplies in town, he met a girl his own age who was also unsatisfied with the choices of her friends and family. She was tiny and delicate, all wide eyes and dainty hands. Her small arms would never be able to swing a hammer precisely, let alone fell a tree and cut it into planks; he wondered how she would build her house. He wondered about his own.

He introduced himself and they got to talking, about their travels, their ideas, what they were looking for in life. They had many similar propensities and took to each other quickly. Over the next few weeks, they saw each other often on the road. His path and her's seemed to cross more and more regularly and he usually helped her strike camp at night; her shelters were flimsy, barely keeping out the rain, and she detested making fires. He was amazed at the strength of will she possessed to make it this far, in spite of what appeared to be a complete lack of the necessary skills.

The months passed, the seasons changed, and they grew to rely on each other. Winter had come. The snows blowing in fast and they hunkered down, together, to wait for the thaw.

Abandoning their temporary shelters, he dug a foundation and put up four walls of sod blocks, topping it off with a roof of oak branches and bark. It was simple and small, but it kept the wind out at night. During the thin air of the early morning, he would hunt, bringing back fresh meat as often as he could. The bulk of the daylight hours were spent goofing off, playing in the cold white and chatting about what they could do once the thaw came. When the sun went down and the wind began to howl, they would huddle together in their blankets and he would tell her stories to drown out her concerns.

Slowly, inexorably, the days lengthened. The snow had lost its annual appeal and the two found themselves with more and more time on their hands. The animals were returning and awakening and food was plentiful; he was even able to find green things for her to eat to satisfy her less-than-carnivorous appetite. Cramped, bored, and increasingly irritable, they began to expand their tiny hut.

One dull morning, she awoke to the rhythmic sound of axe swings, like a raw heartbeat in the gauzy winter sunshine. All that day – and most of that week – he spent felling trees and hewing them into planks which she then sanded and planed. They had no nails, so he worked methodically, cutting notches into each board and fitting them together like a giant jigsaw puzzle. Progress was slow and frustrating. Once started, he attacked the project with a sort of mania, driven to finish it by a deep, intrinsic need to create something out of nothing. She, in comparison, was content to help where she could, not caring about the form of the structure, but merely the function and, as a consequence, couldn't see his concept and often missed a crucial step, forcing him to scrap a day's labor and start over.

The spring thaw found them living in a small house, sleeping in a real bed, cooking in a dedicated kitchen, and storing their leftovers in a dirty – yet tidy – cellar. Their next project was a garden, for which she picked out the items to be planted and he tilled the earth. For a while, they loved their little house and modest existence. The warm sun was a balm for the cabin fever caused by the long months spent in the sod hut, the food from their little garden giving them the simple joy of the fruits of their labors.

Spring pressed on and both occupants of the little house found their discontent growing proportionally with the length of each day. The garden wasn't big enough for her. The house was only one story. He was finding it to be stifling and too warm during the hotter parts of the day. By mid-summer, she demanded that he build a proper house. He didn't take much convincing.

===

He'd always loved his parents' house. It was older than he was and had all the eccentricities that come along with such age. It was worn down to comfort by life and years. When something broke, his mom and dad worked hard to fix it again. It was these aspects that appealed to him; the house was not perfect, not elegant by most means, but it was solid, beautiful, and warm. He loved his house.

But it was not his house.

When the time came, as it does in the life of every young man, he packed up his belongings, slung them across his back, kissed his mother good-bye, and walked out the front door to make his own way in the world and, one day, to build his own home. In addition to the supplies necessary for survival, he carried with him tools: shovel, axe, lighter, rope, saw, hammer. These he would want eventually, when he found just the right plot of land, but they were not the most important tools he carried with him.

In his hands, he had the skills he had acquired over his lifetime, some more useful than others. With these skills, he made his way – foraging, bartering, working, doing whatever he needed to do to continue on his journey. His parents were intelligent, hard-working folk and they had done their best to ensure that he had been given every skill he would need to survive on the road. He possessed a quick, nimble mind, a clever eye, and an easy, sociable nature. No feat seemed beyond his reach.

I tell you this not merely to inform you about this young man's nature, but also as a contrast to the second important tool that he carried with him. In his mind, as most people do, he held a blueprint of the house that he would one day build and a list of all the materials he would want to use in the construction. Some of the ideas he'd gotten from his parents' house, some, from his friends. A few of the concepts were original ideas, never before used in a house of which he knew. Never satisfied with the staples, we was consistently scrapping certain materials in favor of different, less common ones. It was this never-ending search for the perfect construction that drove him, both forward and slightly mad.

===

There are always a lot of people on the road, going all sorts of places in all manners of conveyances. Many of his friends traveled with him for a long time, making discoveries, experiencing hardships, laughing. A few quickly found their plots and settled down to build. He visited as often as he could, offered his help where desired. Eventually, they all parted ways, needing to find their own separate paths.

He kept up communications with a few of them, penning long letters every few months. Once a year, they gathered again in the old glade, trading stories and ideas in the glow of embers and starlight, but every year, fewer returned.

Loneliness began to color his frustration. Everyone around him seemed to have found their ideal settings and had settled down, but he knew that their decisions were not his own and that he could never be happy with their lives. He trudged on.

One day, while picking up some supplies in town, he met a girl his own age who was also unsatisfied with the choices of her friends and family. She was tiny and delicate, all wide eyes and dainty hands. Her small arms would never be able to swing a hammer precisely, let alone fell a tree and cut it into planks; he wondered how she would build her house. He wondered about his own.

He introduced himself and they got to talking, about their travels, their ideas, what they were looking for in life. They had many similar propensities and took to each other quickly. Over the next few weeks, they saw each other often on the road. His path and her's seemed to cross more and more regularly and he usually helped her strike camp at night; her shelters were flimsy, barely keeping out the rain, and she detested making fires. He was amazed at the strength of will she possessed to make it this far, in spite of what appeared to be a complete lack of the necessary skills.

The months passed, the seasons changed, and they grew to rely on each other. Winter had come. The snows blowing in fast and they hunkered down, together, to wait for the thaw.

Abandoning their temporary shelters, he dug a foundation and put up four walls of sod blocks, topping it off with a roof of oak branches and bark. It was simple and small, but it kept the wind out at night. During the thin air of the early morning, he would hunt, bringing back fresh meat as often as he could. The bulk of the daylight hours were spent goofing off, playing in the cold white and chatting about what they could do once the thaw came. When the sun went down and the wind began to howl, they would huddle together in their blankets and he would tell her stories to drown out her concerns.

Slowly, inexorably, the days lengthened. The snow had lost its annual appeal and the two found themselves with more and more time on their hands. The animals were returning and awakening and food was plentiful; he was even able to find green things for her to eat to satisfy her less-than-carnivorous appetite. Cramped, bored, and increasingly irritable, they began to expand their tiny hut.

One dull morning, she awoke to the rhythmic sound of axe swings, like a raw heartbeat in the gauzy winter sunshine. All that day – and most of that week – he spent felling trees and hewing them into planks which she then sanded and planed. They had no nails, so he worked methodically, cutting notches into each board and fitting them together like a giant jigsaw puzzle. Progress was slow and frustrating. Once started, he attacked the project with a sort of mania, driven to finish it by a deep, intrinsic need to create something out of nothing. She, in comparison, was content to help where she could, not caring about the form of the structure, but merely the function and, as a consequence, couldn't see his concept and often missed a crucial step, forcing him to scrap a day's labor and start over.

The spring thaw found them living in a small house, sleeping in a real bed, cooking in a dedicated kitchen, and storing their leftovers in a dirty – yet tidy – cellar. Their next project was a garden, for which she picked out the items to be planted and he tilled the earth. For a while, they loved their little house and modest existence. The warm sun was a balm for the cabin fever caused by the long months spent in the sod hut, the food from their little garden giving them the simple joy of the fruits of their labors.

Spring pressed on and both occupants of the little house found their discontent growing proportionally with the length of each day. The garden wasn't big enough for her. The house was only one story. He was finding it to be stifling and too warm during the hotter parts of the day. By mid-summer, she demanded that he build a proper house. He didn't take much convincing.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)